Many traditional assessments include significant distorting factors like cheating, access to technology/resources, group work, personality differences, attendance, differences in learning time, home-lives, and “apathy.” These distorting factors make many of these assessments invalid tools to determine a final summative grade.

Although many are not valid, some of these assignments may have some value as a learning task or practice event. Valid assessments don’t include distorting factors, respect differences in learning paces, equalize opportunity, and require students to perform with carefully controlled and selected resources.

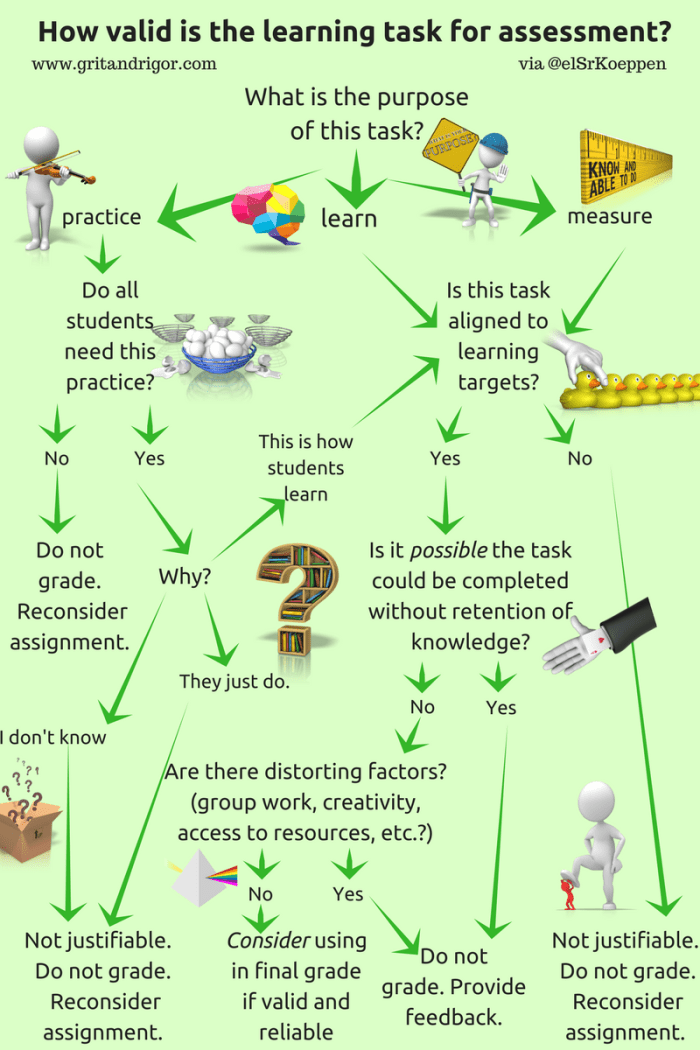

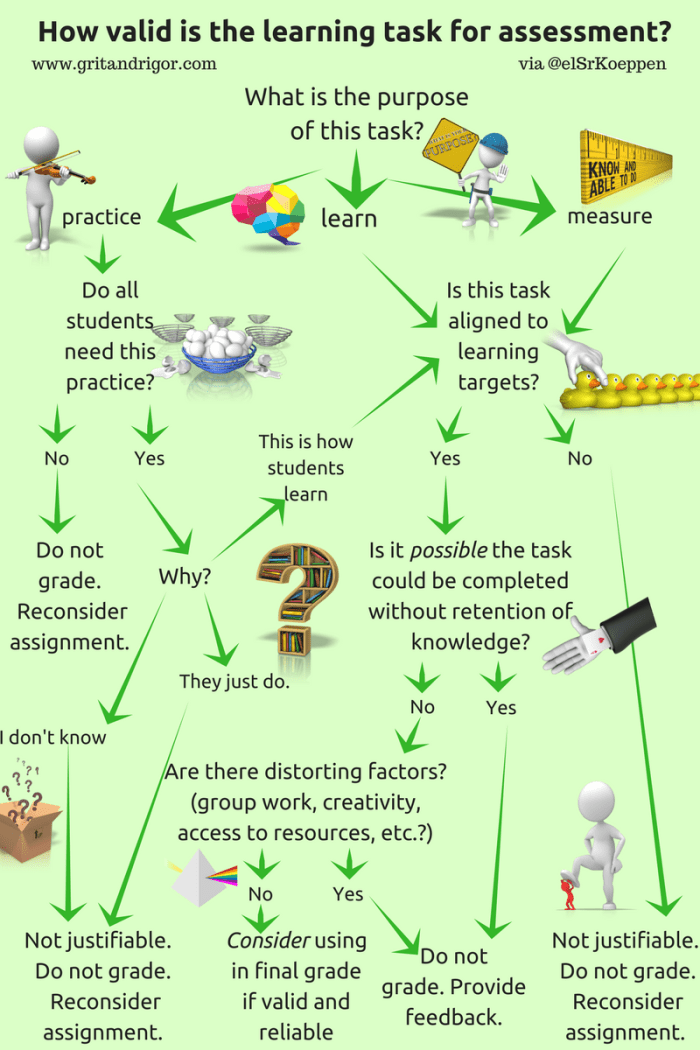

The following are traditional assessments that may end up as part of a final grade but often don’t pass the validity test. (see flow chart at the bottom of this post)

Worksheet (practice) – The primary purpose of this type of worksheet is to provide an opportunity for students to practice the concepts. These don’t tend to require higher level cognitive operations. Often, not all students need this type of practice. Practice  and process should not be graded – the outcomes of this practice and process should be. Reconsider the value of this assignment and who you give it to. Including this type of practice into a final grade is not justifiable.

and process should not be graded – the outcomes of this practice and process should be. Reconsider the value of this assignment and who you give it to. Including this type of practice into a final grade is not justifiable.

Worksheet (learning) – The primary purpose of this type of worksheet is to guide students to discovery of content. Assuming the task is aligned to learning targets, this may be a quality assignment for students to do. This is a process task – as such it should not be figured into the final grade. Give feedback on the observable process. The outcomes and new abilities potentially gained from this task should be assessed separately.

Essay (in-class) – An in-class essay response with careful consideration and control of the tools/resources available to complete the work is often a quality summative assessment – assuming that it is aligned to learning targets.

Essay (out-of-class) – An out-of-class essay response that is aligned to learning targets may be a quality learning task or quality practice. Unless access to resources is  able to be controlled in scope and equitable access is guaranteed, the amount/type of help available to students distorts the outcome. Feedback is important for these types of essays; however, incorporating them into the grade cannot be justified.

able to be controlled in scope and equitable access is guaranteed, the amount/type of help available to students distorts the outcome. Feedback is important for these types of essays; however, incorporating them into the grade cannot be justified.

Project – Projects rarely are summative in nature. Projects tend to be effective tools in helping students learn material in a contextual way. High quality projects also provide opportunities for students to practice using the material in a reflective/high order manner. Projects tend to be complex. The complexity reduces the likelihood that an individual learning task, objective, or standard can be reliably assessed. Projects also tend to span a longer period of time and work is often done not in view of the teacher. Access to resources, technology, and materials further distort the outcomes.

Group Work – It is nearly impossible to determine individual levels of understanding  and ability from a group project. It is unlikely one of your academic standards includes “works well with others.” Group work is crucial to the development of thestudent and is critical to the collaborative classroom; however, it has no place in the final grade. Group work needs to stay in the realm of learning and not assessment.

and ability from a group project. It is unlikely one of your academic standards includes “works well with others.” Group work is crucial to the development of thestudent and is critical to the collaborative classroom; however, it has no place in the final grade. Group work needs to stay in the realm of learning and not assessment.

Bell Ringer – Bell work or bell ringer activities are seen as best-practice. When done well, they are a valuable tool that helps kids focus, review, and connect their thinking. No matter how well done, bell work is not likely to meet the standard for inclusion in the final grade. Most of the time, bell work is “graded” on completion. Simple completion tells very little about what a student knows and is able to do; therefore, it should not be included in the final grade.

Quiz – The curricular timing and specific definition of “quizzes” vary. If the primary focus of the quiz is to check the progress of students, it should not be included in the  final grade. Progress and process have no place in the final grade – the outcomes of the progress and process are what should make up the entirety of a final grade report. If the quiz is meant as a measure of learning and it is aligned to learning standards, it is

final grade. Progress and process have no place in the final grade – the outcomes of the progress and process are what should make up the entirety of a final grade report. If the quiz is meant as a measure of learning and it is aligned to learning standards, it is

possible that it might have value in the final grade picture.

Multiple Choice Test – If the test is aligned to learning targets and it is properly timed, a multiple choice test may be of high enough quality to be a valid measurement of progress. However, multiple choice tests most often are measuring the ability of a student to recognize an answer as opposed to recalling an answer. Recognition requires less of a cognitive load than recall; therefore, it is important to be selective about when multiple choice is used.

Reading Check – Any questions or assessments that are meant to simply check if a student has completed their reading assignment is the same thing as a “completion” grade. There is little valuable information beyond behaviors and habits that this type of assessment provides. These don’t belong in the final grade.

Participation – Requirements of students to actively participate in debates, class conversations, or response to questions don’t respect the diversity of the student base. These are simply completion points and don’t serve much more of a purpose than to give data on student engagement and how out-going a student may be. These points should have no impact on the final grade.

These are simply completion points and don’t serve much more of a purpose than to give data on student engagement and how out-going a student may be. These points should have no impact on the final grade.

If I don’t grade it, will kids do it?

I know for a fact the answer is yes. My students don’t receive grades for their projects or learning tasks. They do the work because they know that it directly leads to acquisition of the material I am holding them accountable for on their recall assessments. Students also understand what my expectations for behavior and productivity are. When a student doesn’t meet those expectations, these situations are handled as a misbehavior with a behavior, not academic, consequence.

See my related posts:

Consider this flow chart when analyzing the validity of your own assessments.

“jerks” isn’t the point – the point is that students have a rational reason to sometimes perceive us as “jerks.”

“jerks” isn’t the point – the point is that students have a rational reason to sometimes perceive us as “jerks.”

and process should not be graded – the outcomes of this practice and process should be. Reconsider the value of this assignment and who you give it to. Including this type of practice into a final grade is not justifiable.

and process should not be graded – the outcomes of this practice and process should be. Reconsider the value of this assignment and who you give it to. Including this type of practice into a final grade is not justifiable. able to be controlled in scope and equitable access is guaranteed, the amount/type of help available to students distorts the outcome. Feedback is important for these types of essays; however, incorporating them into the grade cannot be justified.

able to be controlled in scope and equitable access is guaranteed, the amount/type of help available to students distorts the outcome. Feedback is important for these types of essays; however, incorporating them into the grade cannot be justified. and ability from a group project. It is unlikely one of your academic standards includes “works well with others.” Group work is crucial to the development of thestudent and is critical to the collaborative classroom; however, it has no place in the final grade. Group work needs to stay in the realm of learning and not assessment.

and ability from a group project. It is unlikely one of your academic standards includes “works well with others.” Group work is crucial to the development of thestudent and is critical to the collaborative classroom; however, it has no place in the final grade. Group work needs to stay in the realm of learning and not assessment. final grade. Progress and process have no place in the final grade – the outcomes of the progress and process are what should make up the entirety of a final grade report. If the quiz is meant as a measure of learning and it is aligned to learning standards, it is

final grade. Progress and process have no place in the final grade – the outcomes of the progress and process are what should make up the entirety of a final grade report. If the quiz is meant as a measure of learning and it is aligned to learning standards, it is These are simply completion points and don’t serve much more of a purpose than to give data on student engagement and how out-going a student may be. These points should have no impact on the final grade.

These are simply completion points and don’t serve much more of a purpose than to give data on student engagement and how out-going a student may be. These points should have no impact on the final grade.

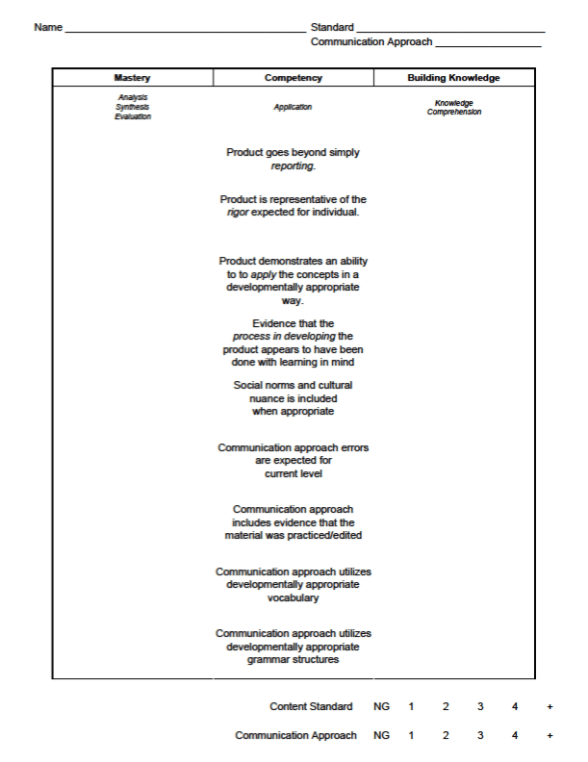

lane rubric doesn’t list all the ways a student can not achieve the expectation. When a student misses the mark, I simply describe how it doesn’t meet the stated goal.

lane rubric doesn’t list all the ways a student can not achieve the expectation. When a student misses the mark, I simply describe how it doesn’t meet the stated goal.